Backgammon

Backgammon is a remarkable dice game that can be played for money. Moreover, Backgammon is a game where success depends not only on luck but also on gaming strategy. In this aspect, it is similar to poker, where skills play a crucial role, especially in long-term playing.

Backgammon is one of the oldest board games and is definitely worth trying. The game doesn't last long (about half an hour), and its basic rules are not overly complicated. We will try to explain the rules to you as clearly as possible so that you can try the game yourself. Based on our experience, the rules of Backgammon, also known as Vrchcáby, are often explained strangely in various sources, especially abroad, and can be challenging for beginners to grasp quickly. We believe that with our detailed and illustrated guide, you will manage. However, refining gaming strategy already requires some practice.

Basic Rules

Backgammon is a game for two players, with one leading (usually) white pieces and the other black pieces. Usually because the colors of the pieces may vary, as brown or red pieces may be seen instead of black ones. However, the color of the pieces does not matter and has no influence on who will start the game, unlike, for example, in chess, where white always starts.

To play, you also need a game board, the graphical representation of which can also vary, two regular six-sided dice, and a dice cup for shaking the dice. Each player often has their own dice in the color of their pieces. The dice cup is probably a measure against cheating or controlled rolls. It is also a rule that neither die may leave the playing area, stand on the edge, on a piece, etc., otherwise, the entire roll is invalid.

Objective of the Game

Each player has 15 pieces. The goal of the game is to first bring all the pieces into your own home board, and once they are all there, to bear them off (remove or bear them out) from the game board. The player who achieves this first wins. The players' paths, based on the values rolled on the dice, are opposite, and that creates the competitive and strategic nature of the game. Players primarily aim for the rapid progress of their pieces and slowing down (blocking) the opponent. We will describe everything in detail.

Game Board

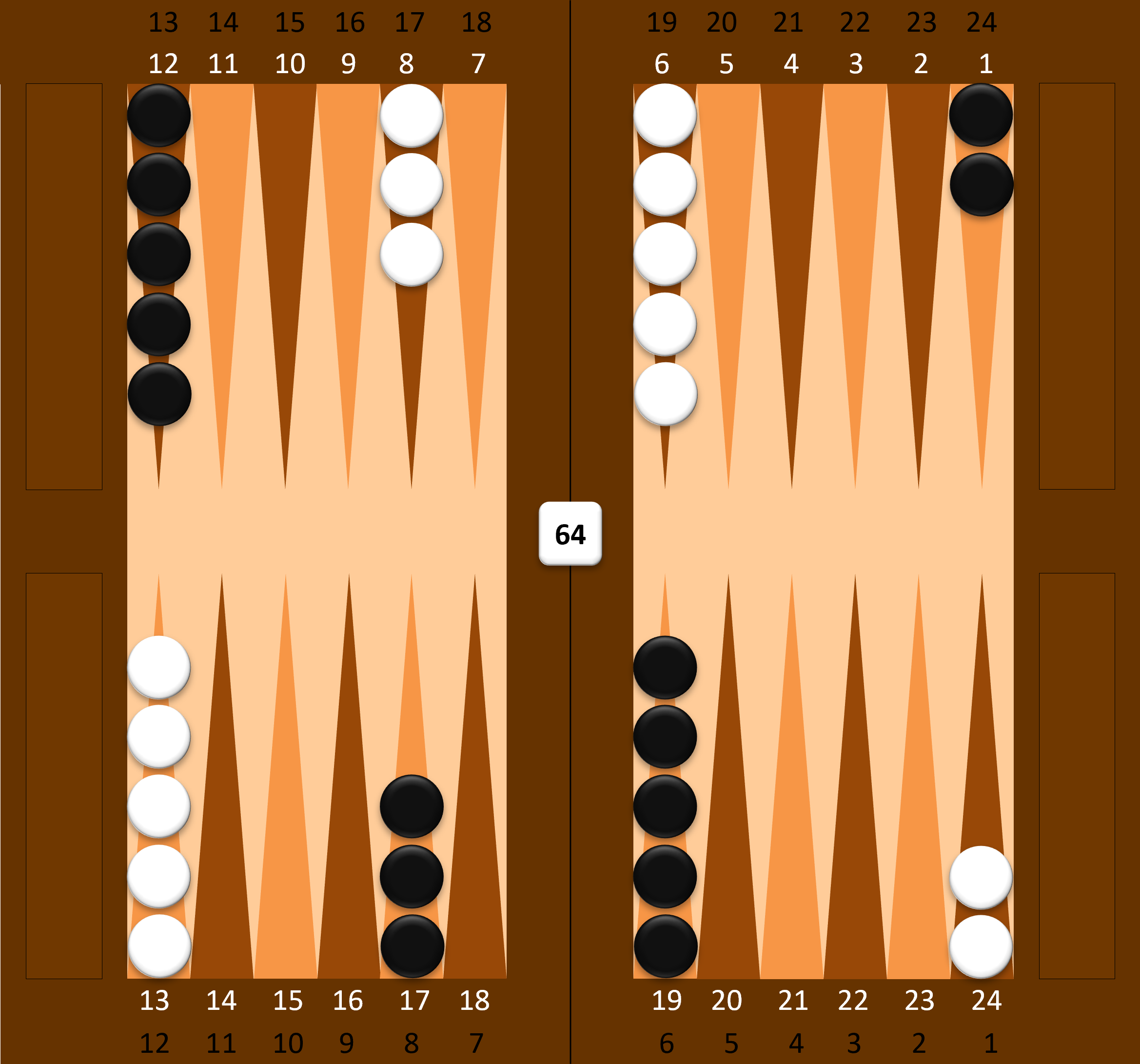

The game board and the basic piece positions of the Backgammon game are shown in Figure 1. As mentioned, players progress in opposite directions along the arrow-shaped triangles or points. The color of the points serves only a decorative purpose, and its alternation is to facilitate counting. Any number of pieces from one player can be on one point (triangle), even all 15 at once (pieces can be stacked on top of each other if necessary).

Figure 1: Game Board and Basic Position of the Backgammon Game

However, a player cannot enter a point where there are already at least two opponent pieces. On the contrary, if a player enters a point that is occupied only by one opponent piece, this piece is hit and placed on the so-called bar. A player who has any pieces on the bar cannot move other pieces until the pieces on the bar are back in play. This occupying (blocking) of points and hitting opponent pieces give the game a strategic character.

For better clarity and educational purposes, the points on the game board are numbered, both for white and black. However, this is not a rule, and some game sets may be completely without numbers, or numbers are indicated only from the perspective of white. There are a total of 24 points on the game board, and their numbers are opposite for white and black: white's one is black's twenty-four (and vice versa) and so on.

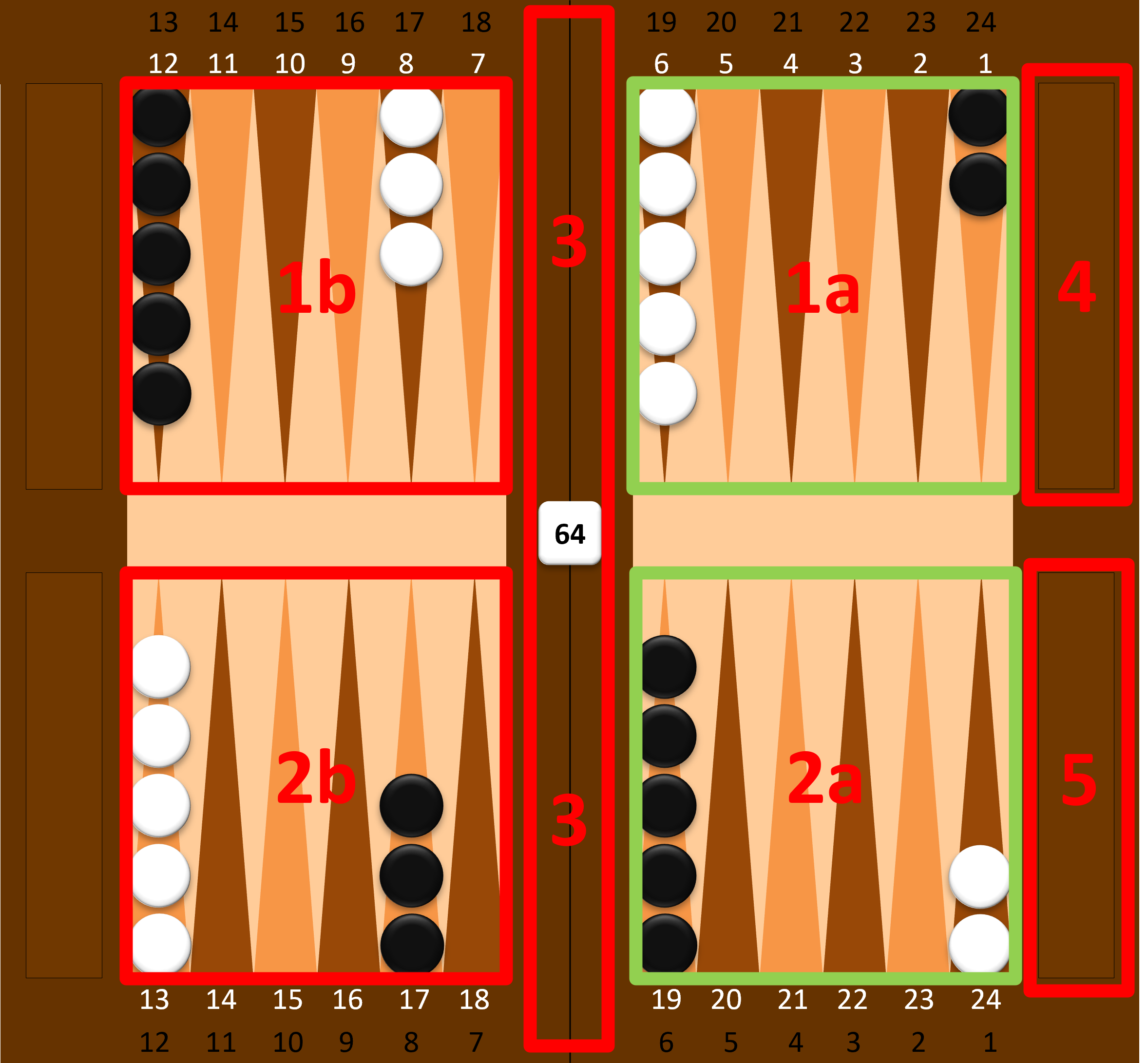

Each player must first bring their pieces into their own inner home board. The white player's own (inner) home board is the space delimited by points 6 to 1 (where all white pieces need to be moved before they can be borne off the game board). The black player's home board consists of numbers 19 to 24 (again from the perspective of white, which are fields 6 to 1 for black). The division and description of the game board in the Backgammon game are captured in the following image.

Figure 2: Imaginary Division and Description of the Backgammon Game Board

Description of the game board in Figure 1:

1a – Own home board or inner home board of white; the space where white needs to bring all their pieces to start bearing them off the game board (thus ending the game);

1b – So-called outer home board of white; it is only for orientation on the game board and when referring to this area when planning strategy or analyzing the game;

2a – Own home board of black; similarly to white, the space where all black pieces need to be brought before bearing them off;

2b – Outer home board of black; the same note applies as for white;

3 – Bar, where opponent hit pieces are placed;

4 – Place (trough) where white borne-off (removed) pieces are placed;

5 – Place for black borne-off pieces (from the inner home board of black).

We can notice that from the beginning of the game, each player has five pieces in their own (inner) home board, and the remaining ten pieces need to be brought there.

The die with the number 64 is used for doubling bets, which we will get to later.

Turns

Players take turns, although later we will see that due to strategic play it may happen that one of the players will not be able to move for some time. Each player rolls their two dice.

At the beginning of the game, however, each player rolls only one die, and the player with the higher value starts the game. If both players roll the same value, the bet being played is doubled, and the dice are rolled again until one of the players rolls a higher value on the die. This player then moves first, and his throw is considered the value he rolled and the value his opponent rolled during the opening roll.

After that, everything proceeds normally: each player rolls their two dice, and advances in their direction along the points, which serve as squares. Stones can be placed anywhere on the point or stacked on each other, but they are usually placed first on the base of the triangle and then additional pieces are added toward the top.

After rolling the two dice, a player can either advance with two pieces – one with the value on one die, the other with the value on the other die, or can play with one piece twice. We deliberately state "twice" because if, for example, you roll 6 and 4, it is not enough to just move a piece to the tenth point from you, but you must first move the piece to the six or four and check if you can enter those points. If both of these points are occupied by at least two opponent pieces, you cannot play with this piece at all (but you can play, of course, with other pieces if possible). This is what distinguishes Backgammon from most board games, where you only need to add up the values on the dice and move that sum on the playing surface.

One more rule applies here. If a player rolls two identical numbers (for example, two fours), they can move doubly, i.e., up to four times with one piece. Of course, they can also move with other combinations, such as three times with one piece and once with another piece, twice with one and twice with another, or once with four different pieces. In all cases, however, it is true, as mentioned in the paragraph above, that the player must split the moves into several steps and always check if they can enter the point.

If possible, the player must always move, even if the move is disadvantageous, and must play as much of the move as possible. If a player can only play one value on the die but not both, they must play the higher one.

Sample Move

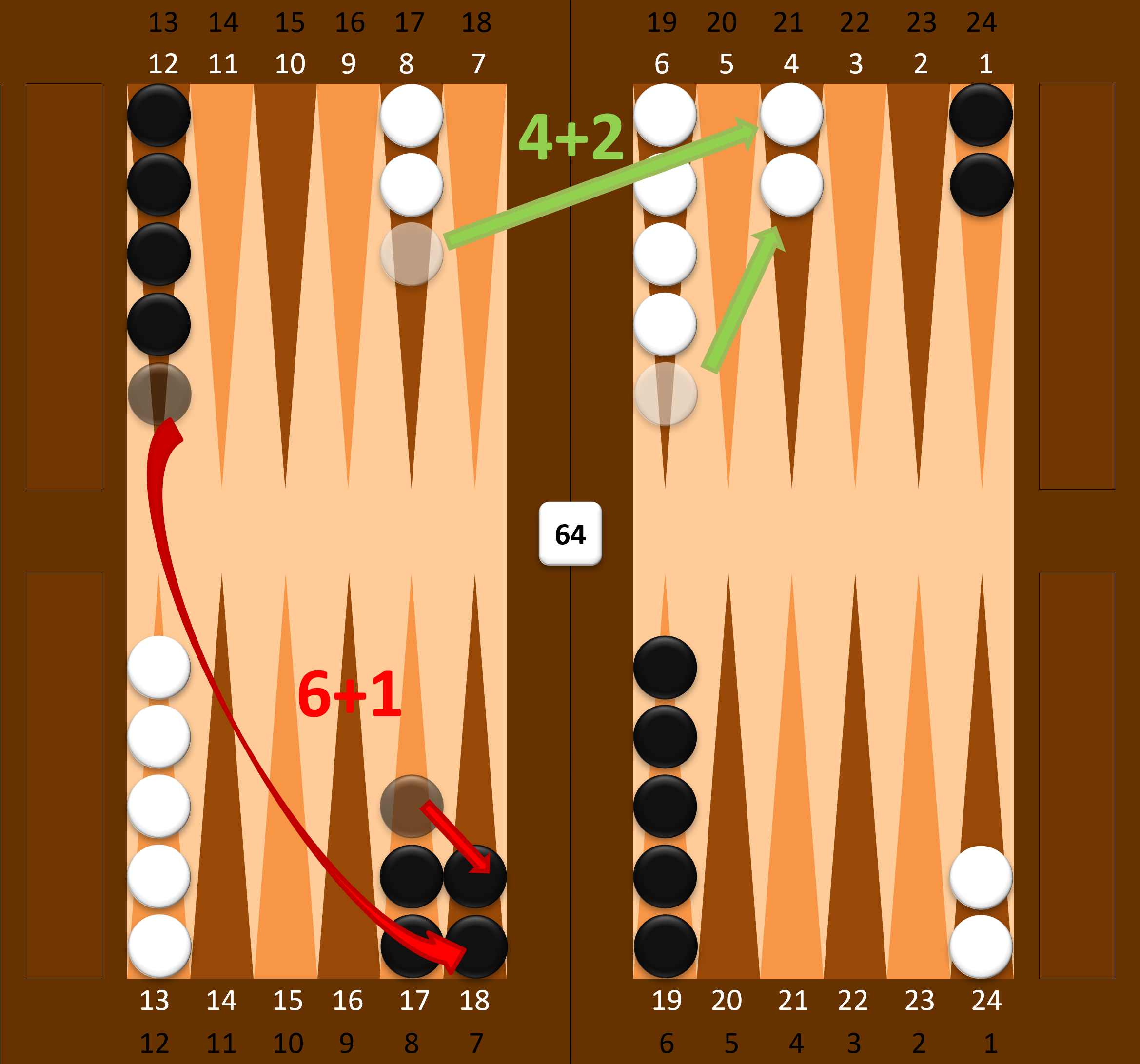

The sample move of white and black is shown in Figure 3. We also clearly see that both players progress in opposite directions. White rolled 4 and 2, while black rolled 6 and 1. The moves in the sample are not the only possible ones. Players can move any of their pieces in accordance with the rules. However, the move of white undoubtedly has its logic: it moves a piece from point 8 to point 4 (i.e., 4 points) and a piece from point 6 also to point 4 (2 points). By doing this, it not only got the pieces into its home board but also "secured" them, meaning they cannot be attacked and hit by opponent pieces.

Figure 3: Sample Move of White and Black in the Backgammon Game

When a point (field) is occupied by at least two pieces, it is sometimes said that a player has made a point. However, this has nothing to do with scoring or deciding something, but it simply means that the player has managed to create a certain supporting point that the opponent cannot enter. We will also get to scoring at the end of the game. Later, we will see that this occupation of one's own enclosure has another meaning.

If Black throws 6 and 1 and also creates a supporting point on field 18 (from White's perspective, 7 from Black's perspective), he could theoretically advance, for example, from field 17 to field 23. However, this piece would be isolated and could be attacked.

Attacking (hitting) and Re-entering the Game

As mentioned earlier, if a field is occupied by only one piece, it can be attacked (hitting) and knocked out. Knocking out is done by placing the piece on the bar in the middle of the board (note: the Backgammon game set is often in the form of a box, and there are hinges in the bar area to close the box).

If a player has a piece on the bar, he cannot move other pieces until he gets the piece or pieces on the bar back into play. The knocked-out piece must go around the entire path again. Even though the piece is placed on the bar in the middle of the board, from White's perspective, we can imagine it as being behind number 24 (imaginary number 25), and it can enter the game through fields 24 (rolling a one) to 19 (rolling a six).

If some of these entry fields are blocked by opponent's pieces, it can be a significant obstacle. If one of the players manages to occupy all entry fields (has two or more pieces on each), this formation is called a "prime", and if the opponent has a piece on the bar, he practically cannot play (or even roll the dice) and must wait until the bar is cleared. An example of a perfect block (prime) is shown below in Figure 6.

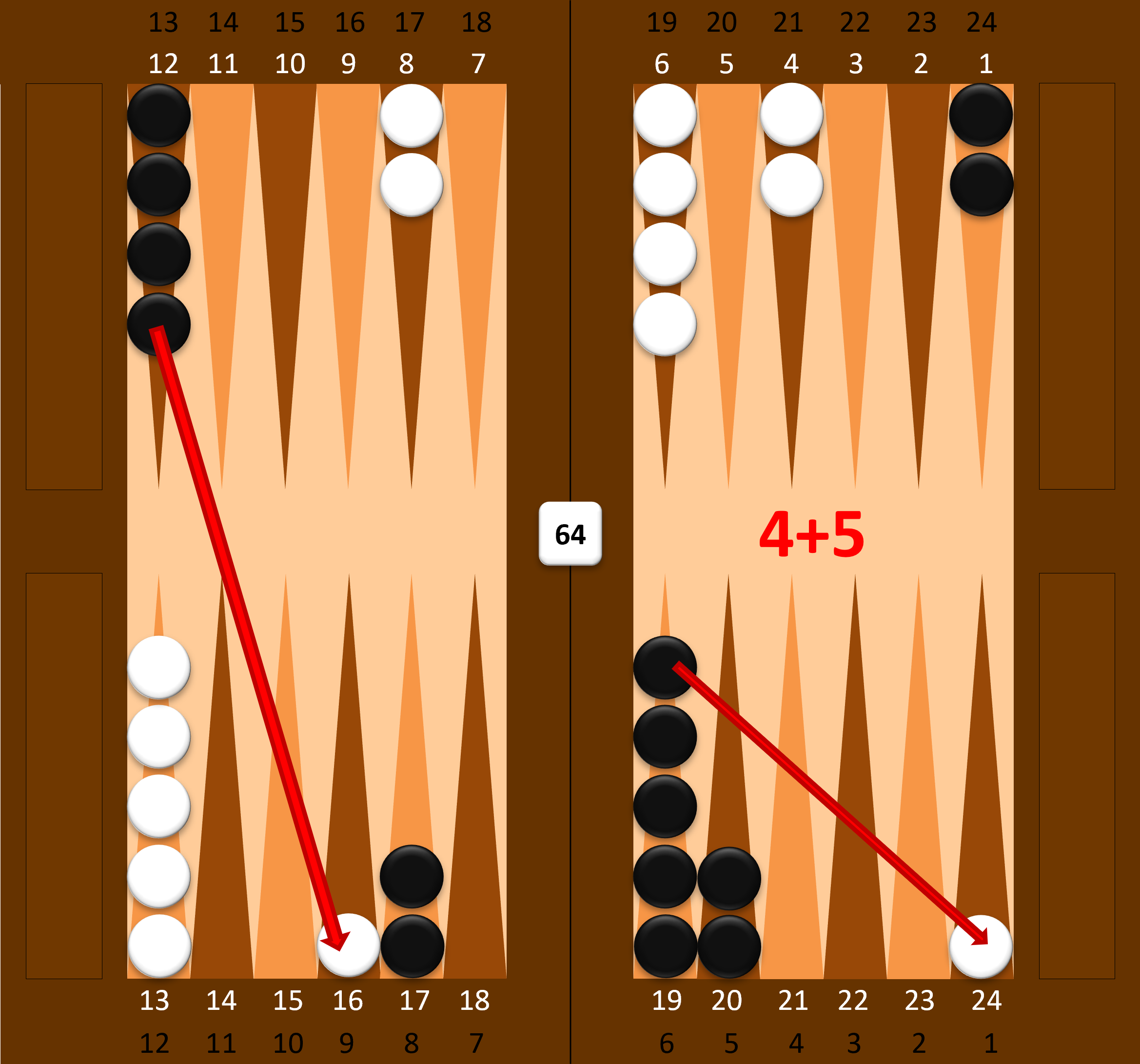

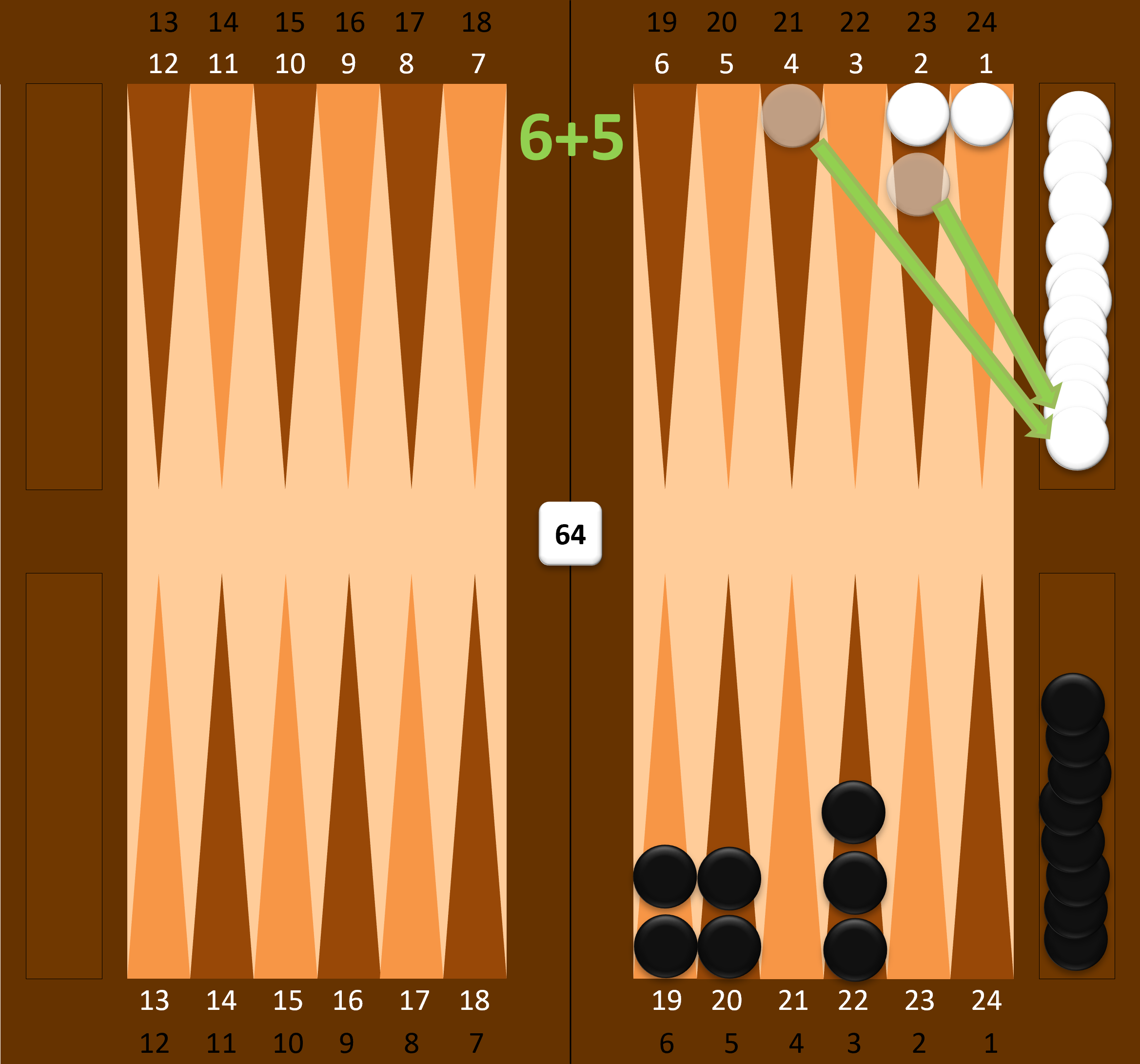

Example of Hitting a Piece

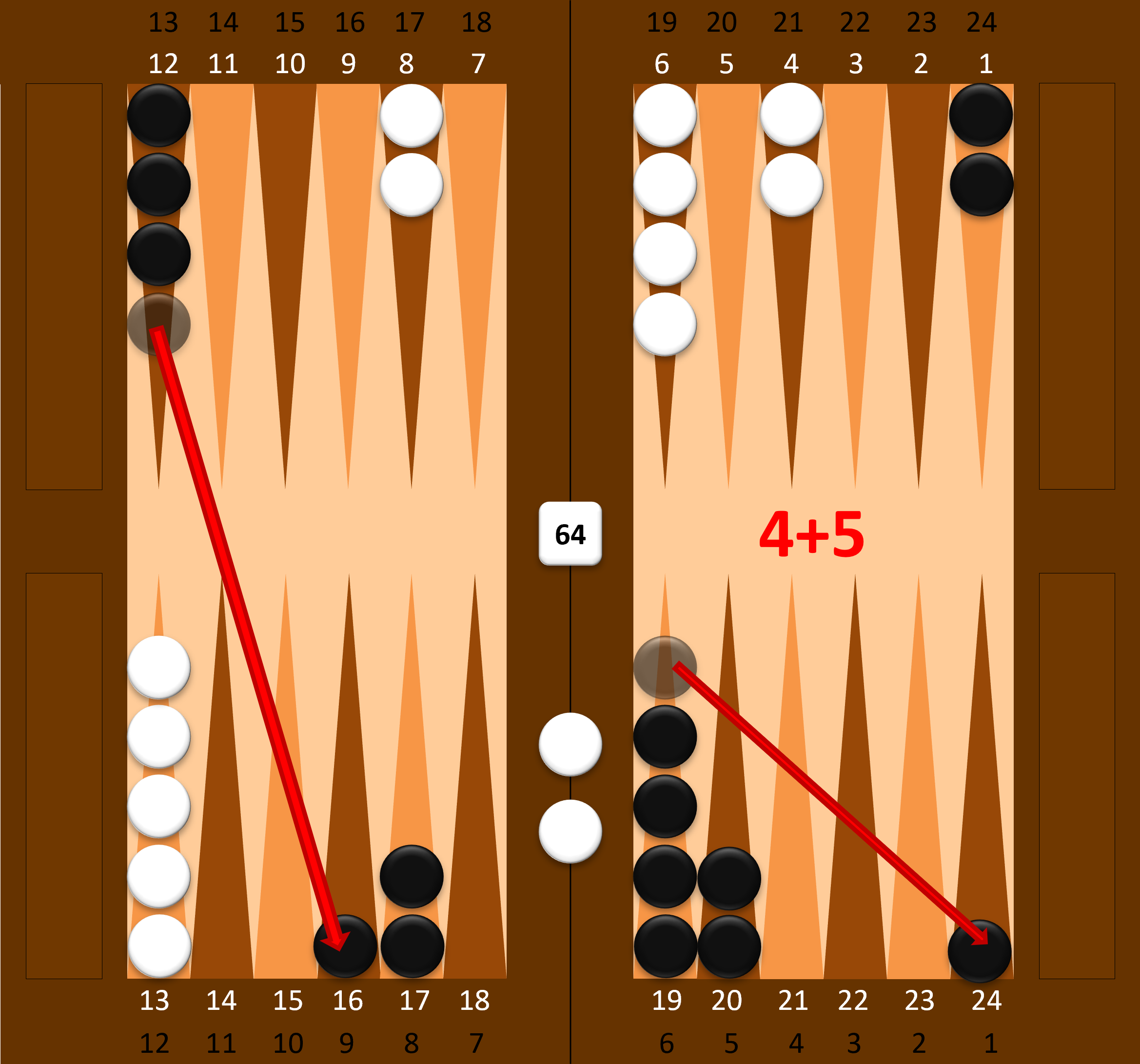

The example of hitting and knocking out the opponent's piece in Backgammon is depicted in the following two pictures. In reality, both steps happen simultaneously. Let's assume it's Black's turn. In the first of the pictures (Picture 4), we see that White has isolated pieces on fields 16 and 24.

If Black manages to roll 4 and 5, he could knock out one or even both of these pieces from White. However, the player must always assess whether knocking out the opponent's piece is advantageous. The picture below is just illustrative, not the best possible move.

For example, knocking out the White piece from field 24 would be very questionable, as White could re-enter the game with a roll of one and eliminate the Black piece, which would then have to go through the entire path again (and it was already in Black's own enclosure).

Figure 4: Example of Possible Hitting (Knocking out) a Piece in Backgammon

Let's assume that Black indeed rolls 4 and 5 and makes the move as shown in Picture 4. He moves one piece from field 12 to field 16 (by 4 spaces) and knocks out the White piece to the bar. Similarly, he moves the piece from field 19 to field 24 (by 5 spaces) and knocks out this White piece to the bar, as shown in Picture 5.

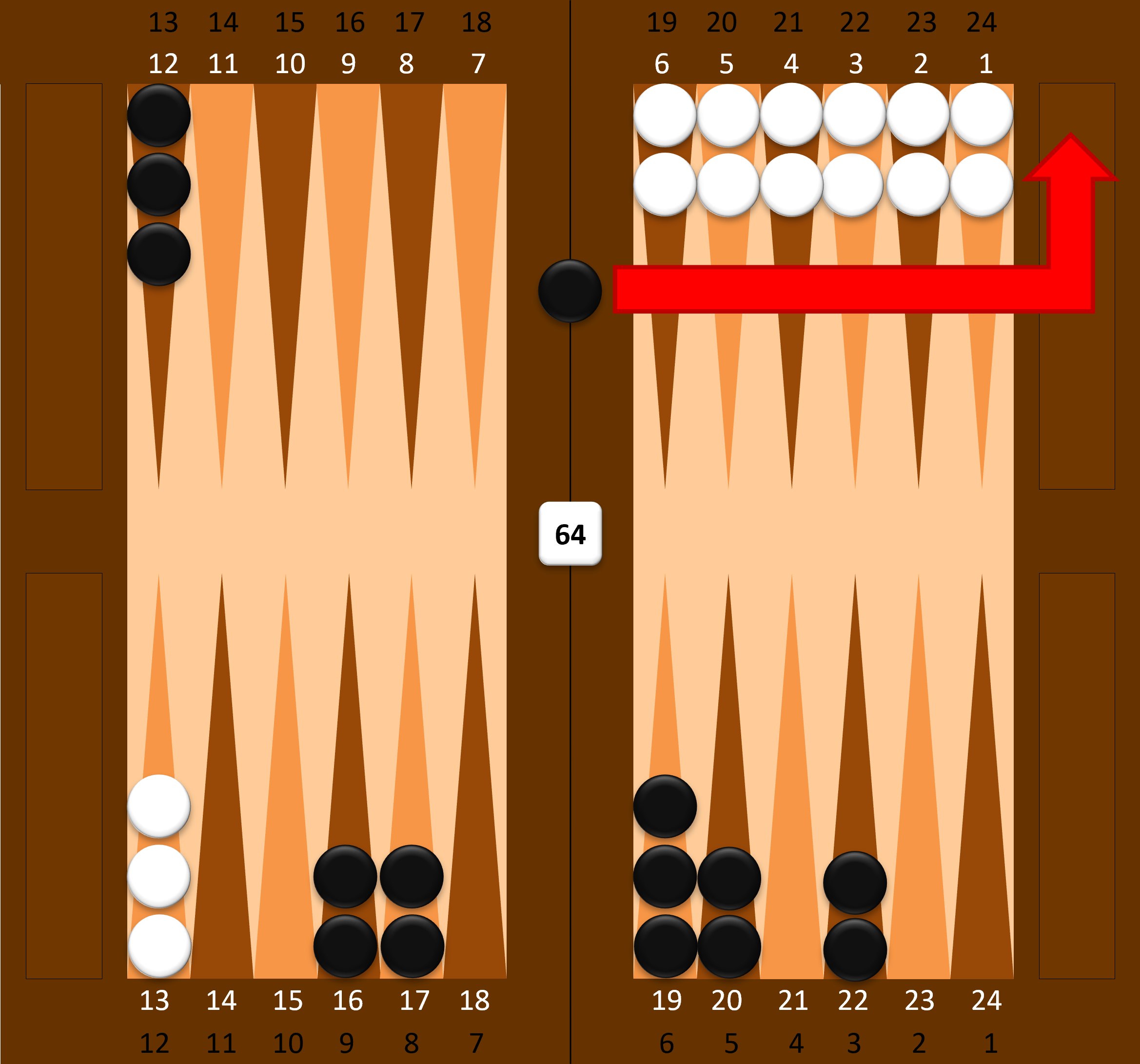

Figure 5: Completion of the Example of Knocking Out a Piece – Moving Black Pieces and Relocating White Pieces to the Bar

White cannot move any other pieces than those on the bar. He must get them back into play (re-entering). We can imagine that the White pieces on the bar are on the imaginary field No. 25, i.e., the farthest from the goal, i.e., the own enclosure of White consisting of fields 1 to 6.

White rolls two dice. If a one appears on either die, the piece is moved to square 24; on a two, it goes to square 23; on a three, to square 22, and so on. Squares 19 and 20 are blocked by black, so if, for example, white rolls 6 and 5, they cannot move past the blockade.

However, they could roll, for instance, 1 and 5. They would move one piece to square 24, potentially knocking off the opponent's piece, and the five would be forfeited since other pieces cannot move until one is in the opponent's home board. Black enters the game through squares 1 to 6, which are the furthest squares 19 to 24 for them. Even this area is partially blocked.

Blocking Opponent's Pieces. Prime Position

A perfect block equals the aforementioned prime, depicted from white's perspective in image 6. Black has one piece in the opponent's home board. The red arrow shows how black would return to the game. However, at this moment, they cannot enter the game since all entry squares are occupied by at least two pieces. Black refrains from rolling at this point and must wait until space is available in white's home board (remember that black cannot play other pieces if one is on the bar).

White would probably move the other pieces from square 13 into their home board and then start bearing off. This would free up some squares, allowing black to re-enter the game and potentially knock off a white piece if left isolated.

Figure 6: Example of a Formation Called Prime (from White's Perspective), Preventing Black from Entering the Game

Bearing off Pieces from the Board

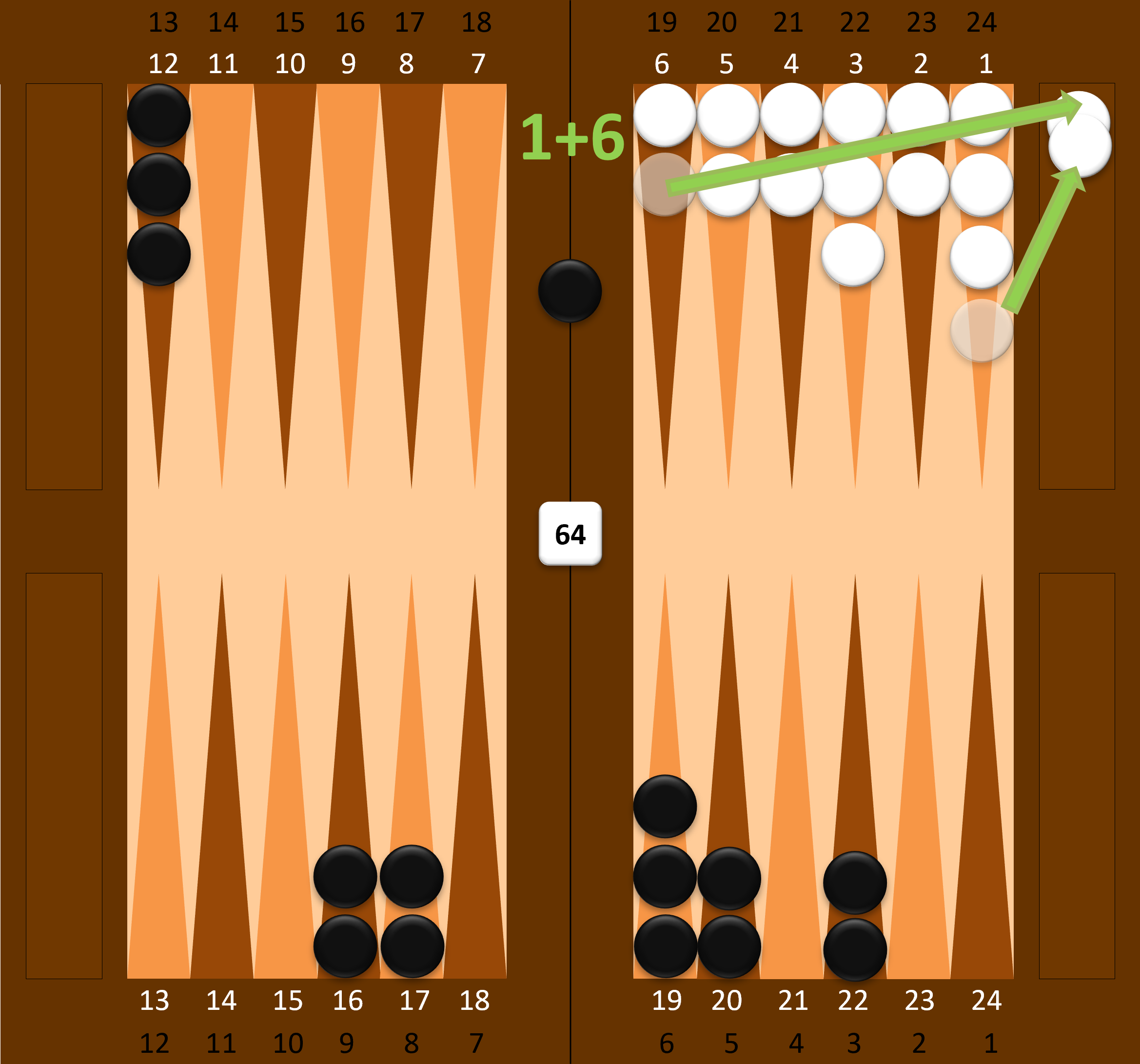

Once a player has all their pieces in their home board, they can start bearing them off, i.e., remove them from the board. For example, from white's perspective: all pieces don't have to be spread across all squares 1 to 6; they can be on any of these squares and in any quantity. It could be all 15 pieces on square 4, for instance.

Pieces are removed based on the roll of the dice. However, if a player rolls a higher value than their furthest piece, they can remove a piece from the furthest square. This rule only applies inward toward square 1 and wouldn't if the player rolled a value corresponding to an empty square but with other pieces behind it. Examples will clarify this.

Figure 7 depicts a simple situation. White has all pieces in their home board, and all its squares are occupied. Regardless of the roll, a piece can be removed from square 1 and another from square 6. However, notice that white would weaken their position on square 6, as that piece would be isolated and could be hit (if black rolls a 6 to re-enter the game).

Figure 7: Example of Bearing Off Pieces from the Board in Backgammon

It would be better for white to bear off one piece from square six and move the other one by one square to square five (instead of bearing off a piece from square 1). This way, they wouldn't jeopardize any of their pieces, maintaining a solid blockade (black could only re-enter through square 6).

In the situation shown in image 8, white has already removed some pieces from the board. Squares 6 and 4 are empty, and these are also the values rolled by white. The two furthest pieces are on square 5. White rolled a 6, which is farther, so one piece can be removed from square 5. The value on the second die is 4, and that square is empty. White has one more piece on square 5, but its roll (4) is smaller (closer or not furthest), so it cannot be removed and must advance four squares to square 1.

Figure 8: Another Example of Bearing Off Pieces (Removing Pieces from the Board)

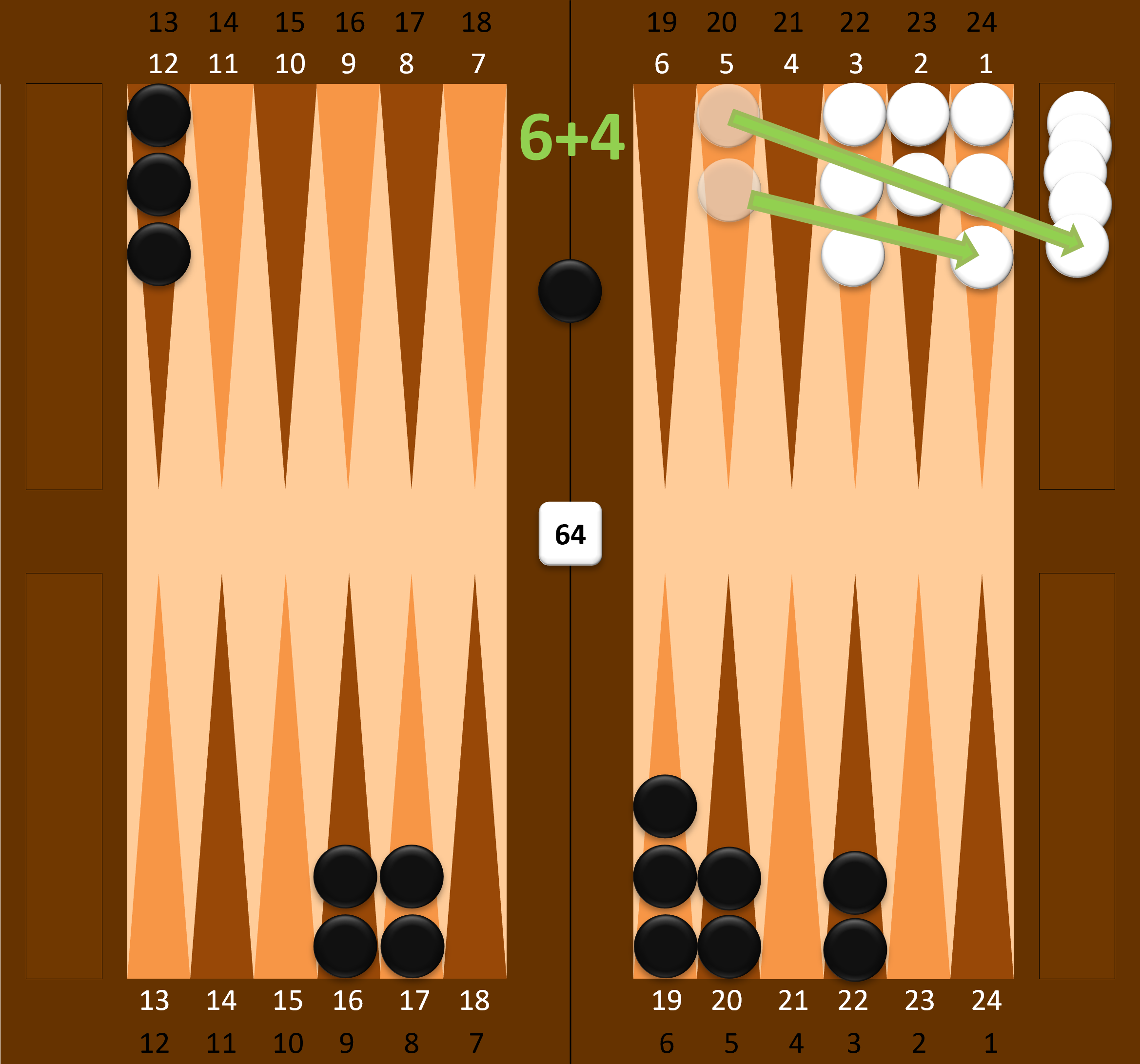

In this new situation in image 8, white could roll anything and remove at least two pieces from the board. Even in bearing off pieces, it's advantageous to roll two identical values on the dice, as a player can remove up to four pieces if possible. For instance, rolling 6 and 6 would remove three pieces from square 3 and one piece from square 2. Two identical values significantly expedite "bearing off."

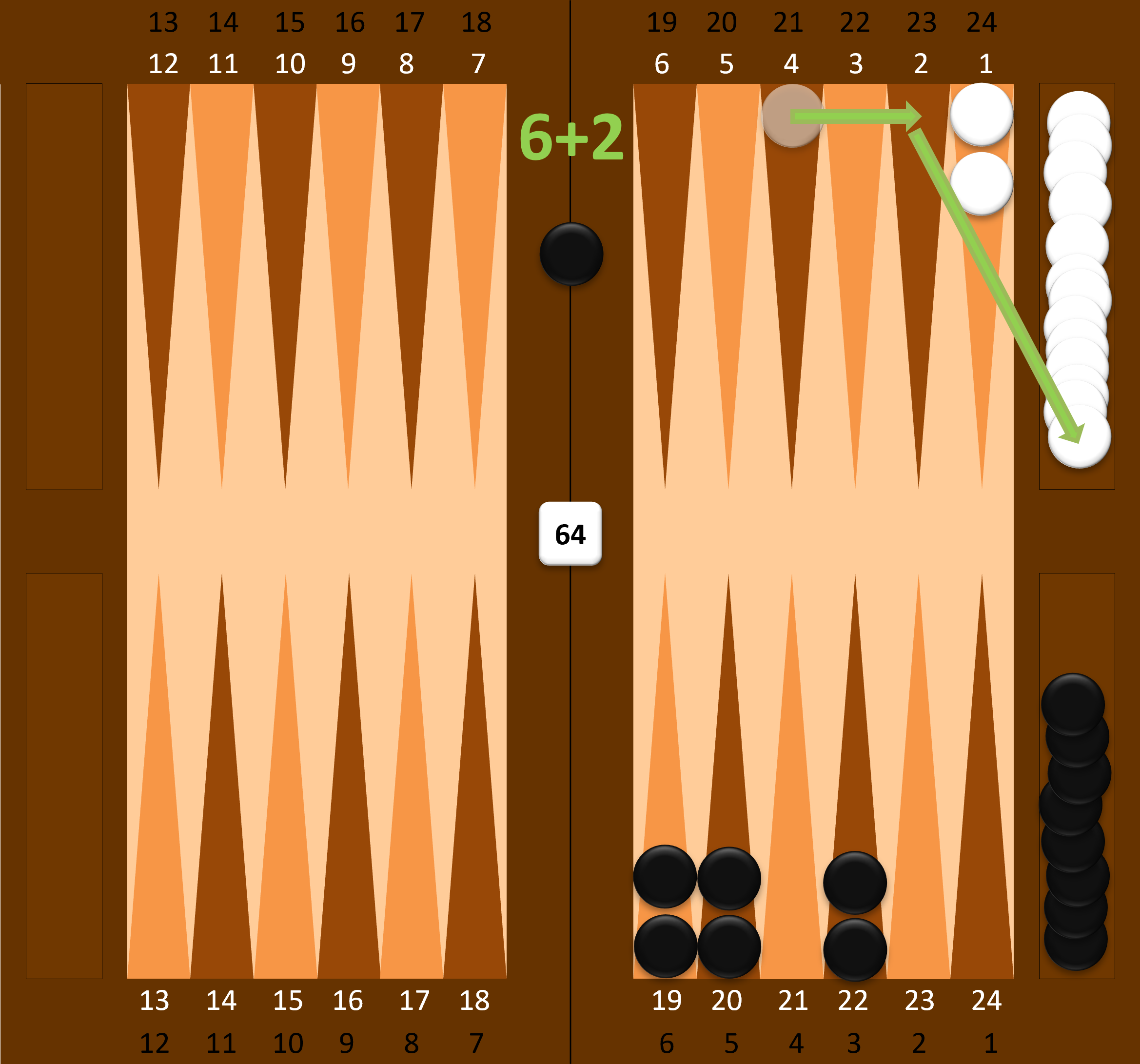

Figure 9 illustrates another possible situation with higher dice rolls. White rolled 6 and 5, and even though there are no pieces on these squares, they can or will have to remove the two furthest pieces from squares 4 and 2. Squares 2 and 1 have isolated pieces, but at this moment, it doesn't matter since the opponent has no pieces on the bar and cannot hit them.

Figure 9: Example of Bearing Off Pieces with Higher Dice Rolls

Figure 10 is the last but strategic example of leading the game in bearing off pieces. White rolled 6 and 2 and could theoretically remove one piece from square 4 and one from square 1. However, this would leave only one piece on square 1, and notice that black still has one piece on the bar. If black rolls a one, they would hit the white piece to the bar, and it would have to travel the entire route again. This move would be quite risky. However, white can play much better by splitting the move into two steps. First, move a piece from square 4 two squares to square 2 and then roll a six, removing the furthest piece from square 2!

Figure 10: Example of Strategic Gameplay in Bearing Off Pieces, Opponent Has a Piece on the Bar

The game ends, and the player who first bears off all pieces from their home board wins. The game can also end by a player's resignation, which the opponent may or may not accept (considering scoring).

Scoring at the End of the Game

In Backgammon, there are three types of victories. The winning player can earn one, two, or three points (and thus single, double, or triple the stake) depending on the margin of victory.

- Simple or normal victory. The winning player gets 1 point (a single stake) if their opponent manages to bear off at least one piece.

- Gammon. The winning player gets 2 points (double stake) if their opponent fails to bear off any pieces, and the condition for a triple victory (Backgammon) is not met.

- Backgammon. The winning player gets the highest victory of 3 points (triple stake) if their opponent fails to bear off any pieces and simultaneously has at least one piece in the opponent's home board or on the bar.

The above applies if the stakes haven't been increased. The next chapter deals with raising the stakes. If the stakes were doubled, the point gains described above would also be doubled, and so on.

Bets and Raising Bets

Bets, especially the possibility to double (double), give the game a slightly more challenging character. A special die with the number 64 is used for raising bets, also known as the doubling cube (doubling cube). At the beginning of the game, it is placed in the middle of the bar. The doubling cube has the classic six faces, but it has values of 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, meaning the higher value is always the double of the previous value.

If a player believes it is advantageous for them (or it can serve tactical or intimidation purposes), they can offer to double the bets. This must be done before their turn, before rolling the dice, by turning the die with the number 64 to the value 2 and moving it to the opponent's side of the bar. The opponent now has only two options: either accept the bet or resign.

If the opponent accepts the bet, the game continues, and it is they who can (but do not have to) double the bets further in the next moves. They turn the die to the number 4 (again before their turn) and move it to the opponent's side of the bar.

Luck can be fickle, and players can alternately double the previous bet. The player must carefully assess not only their own doubling possibilities and the right moment but also the opponent's offer to double the bets. The opponent may not always behave completely rationally but may simply be trying things out. Experience and steady nerves play a role in these situations, similar to Poker.

Good assessment of one's own possibilities and timing of the double is also important because an ill-considered double could give the opponent the opportunity to resign, while it would be much more advantageous to continue the game, as they could win with a gammon or backgammon and thus gain double or triple the bet.

The value on the doubling cube multiplies the basic bet made before the start of the game. Considering that there are three types of victories, with backgammon being a triple win, bets can rise quite high. For example, if players played for a basic bet of $10, then by the third cube, the basic bet would multiply to $80. And if one of the players lost with a backgammon style, they would have to pay the opponent $240 (triple the basic bet).

Conclusion

We have successfully covered the basic rules of Backgammon. We hope it was understandable for you, aided by the numerous illustrations. Now you can try playing this exciting game and discover strategic elements such as blocking and ejecting opponent's pieces, quickly advancing into your own home board, safely bearing off pieces, and more. We will return to the strategy and probability in Backgammon in some of the upcoming editions. Matches and tournaments are held in the game, and players have their ratings similar to chess players.

In short, Backgammon is an ideal game for players who enjoy both the skill and luck elements. Similarly to poker, skill inevitably manifests itself over the long term. Thanks to luck, a weak (or worse) player can defeat anyone, but not consistently. In the long run, skill triumphs over luck. If you have learned to play Vrhcáby from our website or simply like the presentation of the page, we would appreciate it if you gave it a "like".

You Might Be Also Interested

- News from the World of Gaming

- Chess Rules and How to Play Chess for Money

- Fair Bet – What Is, Meaning and Examples

- Black Jack Rules, Basic & Advanced Strategy

- Poker Rules, Games and Strategies

- Bet on Gold – Is Gold a Bubble?

- Gambling Game Definition & Criteria

- Craps – The King of the Dice Games

- Dice Games | Casino-Games-Online.biz

Based on the original Czech article: Vrhcáby (Backgammon) – kompletní pravidla srozumitelně.